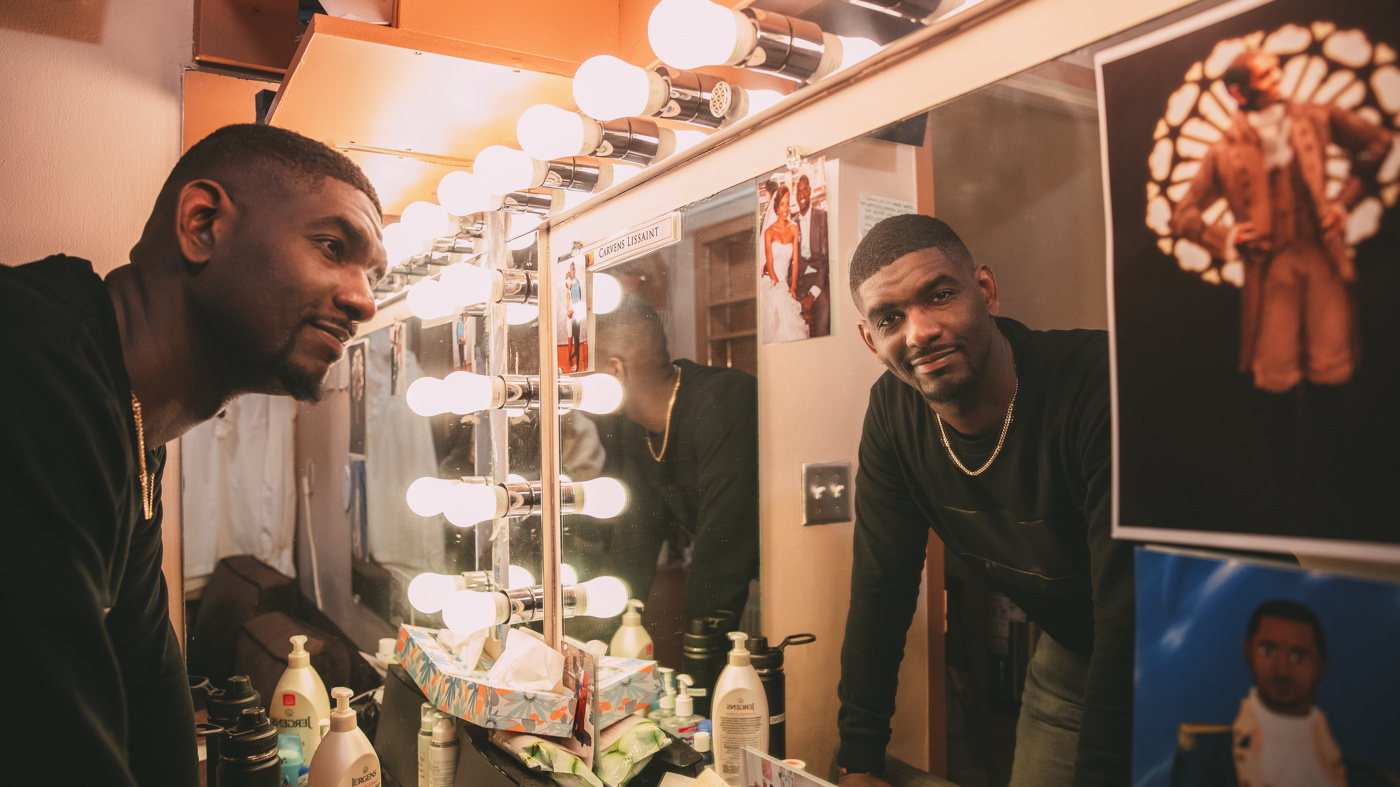

(Photo by Caitlin McNaney for Broadway.com)

Hamilton’s Carvens Lissaint Takes Aim with His New Book of Poetry and Shares His Story of Rising Up

"Young, scrappy and hungry" are the adjectives Lin-Manuel Miranda memorably uses to describe Alexander Hamilton in Hamilton, but he could have just as well been talking about the teenage years of Carvens Lissaint, the Broadway newcomer who plays George Washington in the game-changing musical. When his Haitian parents came upon hard times and lost their apartment, young Lissaint took to the subways with his love of spoken word poetry, staying up all night riding the lines and making whatever he could showing off his newfound talents. Now, Lissaint has taken his skills to a larger stage, without losing his scrappiness or hunger—if anything, the Broadway experience has given him even more to say. On the latest episode of Front Row, Paul Wontorek sits with the ambitious newcomer to talk about his incredible journey and the release of Target Practice, the striking just-released album and book of his newest writings.

Tell me about the first time you got up and performed a poem in front of people.

Oh, we’re taking it all the way back. [Laughs.] I was 16. I went to an open mic at the Whitney Museum. I don’t even remember the poem—I think it was terrible—but what I remember was the overwhelming support by the other young people there. I thought, “Wow, this is a community that champion’s the youth’s voice. This is something I need to be a part of for the rest of my life.” Really, it was that simple.

What were you writing about? What did you want to get on the page and on the stage?

At the time, I was just writing my teenage feelings—Man, the world sucks! School sucks! And I wrote a lot of love poems—I was very romantic. But I was also political real early. I had a mentor named Mahogany Brown. I remember I wrote this poem, and she said, “This is beautiful, but I’m going to tear this up, because I don’t think this poem cost you anything.” So I always knew I had to come to the page with high stakes, that anything that I wrote had to be a matter of life and death.

There’s a lot of life or death in your new book, Target Practice. How did it come about?

I started writing this in grad school, originally as a play. We were doing a production of Buried Child and I was playing Father Dewis, so I had a lot of offstage time! [Laughs.] Really the genesis of the book started with the death of Philando Castile, the man in Minnesota. He was in the car with his girlfriend and his girlfriend’s daughter in the back. He respected a lawful order, effectively communicated that he had a firearm in the car, that it was licensed. And still he was deemed as someone who was a threat, even with a child in the car. I saw the video.

That video is hard to forget.

I saw it live, while backstage doing the show. And I said, “I have to write.”

The poem that the video of Philando Castile inspired is actually where the title comes from.

Yeah. “Is the black body target practice?” It’s something that I’ve wrestled with all the time, because we’re targets in many ways. It can be violent or nonviolent. It can be micro-aggressions. And really, it just goes through my narrative of different stories of racist experiences that I’ve had. Walking into my apartment building, or on the train, or sitting at dinner with my wife.

Or, you’ve said before, at the stage door of Hamilton.

Or at the stage door of Hamilton. Or fans who comment on my Instagram and say, “Oh my God, I loved you as George Washington, but I don’t really know about this racism stuff you’re talking about. Racism is like over.” [Laughs.] You know, there are people who love Hamilton and hate black people. It’s real; I’ve experienced it. So I had to speak out about it. I had to. And I love that Hamilton is giving me the platform to be able to speak about this.

Are these scary thoughts for you to share? Are you nervous about being in the biggest hit in recent Broadway history and saying these things?

At first, yeah. Because you start to think about your livelihood. If I start putting the mirror to the faces of the people who may be implicated in some of these actions, will I ever work again? But I never started this work for fame or for money. I always did it because I had something to say and the truth needed to be told. And I felt like I was called by God to speak to higher issues for the marginalized, oppressed and people who don’t have voices for themselves. That’s why I started this work, and that got me to Hamilton. Nothing else did. God brought me Hamilton. So there is no fear.

Your life seems blessed in many ways right now—amazing Broadway job, loving home life with your wife, newfound attention for your talents. Yet you seem to have a great ability to not allow yourself to get comfortable.

I think enjoying life is important, but I think enjoying life and comfort are two different things. Comfort can sometimes be complacency and it’s just not in my bones. I’m from a rich history of hardworking, Haitian immigrant people who didn’t have food to eat, water to drink, a place to live—basic amenities that I think ever human should have. So, how dare I sit in complacency when I know I have family out there that don’t have the mere blessings that I have here?

What are you parents like? I know in the late '70s, they came to New York from Haiti. What do you know about their early days in the city?

I don’t know much. My father was the last of his brothers and sisters to come here. His older sister was here first and helped him get here. My dad said he came here on a Friday and was in school on Monday.

Wow.

He was like, “I need to make a better life of what I’ve had before. I need to do that for my family and myself and for the future kids.” I don’t know all the stories, but I know that man was in school. He was also working a night job and he just never stopped working since. Even to this day. I’m like, “You just need to retire.” And he’s like, “No, I have to work.”

What does he do for work?

He’s a desk attendant at Barnard College up at Columbia University. He works nights at the dorms, making sure everyone is safe. My wife said, “Hey man, you need a break.” And he looked at her and said, “Break? What is a break?” Like, he literally in his head, he was like, “I don’t know what a break is.” It’s an honorable virtue that I think was instilled in me in a lot of ways.

You’re your father’s son.

Very much so.

Tell me about the night he came to see Hamilton.

He just broke down and weeped. I’ve seen him cry maybe three times. And I don’t think I ever hugged my dad, but he broke down in my arms and held me at the stage door for about two minutes. And that’s a long time! It was so moving for me. To see that I affected him in any type of way, and for him to feel there were things that he instilled in me that helped me get there…Yeah, it moved me. I still haven’t unpacked that moment. It was probably one of the most beautiful moments I’ve had with him.

Finances got tough for your family when you were a teenager.

Yeah, we hit a real financial rut. The company that my dad was working for as a computer technician went under, so he was out of work for a really long time. I don’t know if that increased our debt or it was mismanagement of money, but he didn’t have enough to afford where we were living. Gentrification hit our area really, really hard. People were buying up real estate, fixing things up and kicking the black and brown people out. Luckily, we had a lot of family in the city, so were able to couch hop for a bit. But we didn’t have a home. I never asked my parents for money; I went out and tried to get it myself. Performing on trains, always competing in poetry slams… Literally taking my last $7, going to Nuyorican Poetry Cafe and paying that $7 to get in and praying that I won the poetry slam. If I won, I would get like $10 or $15 and I knew I had enough money to get a slice of pizza and a MetroCard to go back home and do it all over again. That’s what I did for years. I didn’t sleep in a bed for like three years, from 2008 to maybe 2011.

You’d sleep on the trains?

Ride them all night—ride it all the way up, ride it all the way down. It was a rough time, but it instilled a lot of discipline and a lot of gratitude. Because I don’t need much. Basic amenities for me. Do I have some food in the fridge? A roof over my head? T-shirt on my back? If I have that, then I’m good. My wife has to force me to buy new clothes. She’s like, “You look crazy! That has a hole in it. Please don’t embarrass yourself. Buy some new clothes!” [Laughs.]

(Photo by Caitlin McNaney)

You discovered In the Heights—and Lin-Manuel Miranda—around the same time.

At high school, I was part of a salsa dance team for gym credit. They took us to this off-off-Broadway show called In the Heights, maybe like eight or 10 of us. I get to the theater and see the set and I’m like, “That looks like a bodega! That looks like my block. That’s dope. This looks like where I’m from!” I was immediately blown away by that. Then you hear the first beats and it’s salsa! And Lin comes out and starts rapping and we’re like, “Wait a minute!” We’ve just never seen anything like that. And then all these black and brown and Latino people came out dancing. I was just blown away. But the game changer was seeing Christopher Jackson, this smooth black brother singing this sultry, smooth R&B. I was like, “Y’all, there’s room for me!”

And you eventually met him.

I had the opportunity to meet him because my best friend, Joshua Bennett, performed at the White House with Lin when he debuted…

...What was called “The Hamilton Mixtape”.

Yeah, the mixtape. And Lin gave him tickets to see In the Heights. I’d already seen it a couple of times, but I was up in the nosebleeds, not in the orchestra! We went backstage and I got to meet Chris. I’m like, “It’s an honor! You’re the reason I’m acting!” He was amazing, and we became friends on Facebook. And he helped me with undergrad auditions. I was like, “Yo, man. I need an upbeat song. Can I get ‘Benny’s Dispatch’?” He said, “Meet me at the stage door.” And he gave it to me. Always giving me advice. We rarely speak, but every time we do, it’s something beautiful and profound.

And now you’re on Broadway.

On it! Of it.

But that’s not all. You’re on that same stage where you saw In the Heights, playing George Washington, the role that Christopher Jackson originated…What does it mean to walk into that theater? It’s your life now. The dazzle may have worn off a bit.

Definitely, the dazzle is gone. Because it’s work, man. It’s work, and it’s hard work. Everyone is tired, everyone is injured. But I make sure I don’t lose that sense of the dazzle, if you will. I have a letter that Chris Jackson wrote to me when I joined the show. I have it posted right on my mirror. Sometimes you have to build a monument to remind you where God has brought you from and where God is bringing you to. For me, that’s important. But it’s so athletic, it’s such a sport. When I walk into the theater it’s like what LeBron James must feel like when he walks into the Staples Center. “I’m tired. My body hurts. But yo, it’s time to go.” There are thousands of people there. I walk by them before I walk into the stage door. And it gives me a sense of urgency and excitement. It makes me hype. I’m just trying to remind myself—I came from the bottom and I’m here now. And I’m just trying to do the work.

Watch the full Front Row segment on Carvens Lissaint below.

Interview was edited for clarity.